Rethinking drug laws in a new global moment

While so much of the world’s attention is focused on the aftermath of the US Presidential election and the transition of power to President-elect Biden, I was excited to see some of the other outcomes of this year’s US election. Voters in several states embraced sensible drug policy reforms that will make a huge difference to people’s lives, take the burden off criminal justice systems, improve public health and, ultimately, save lives.

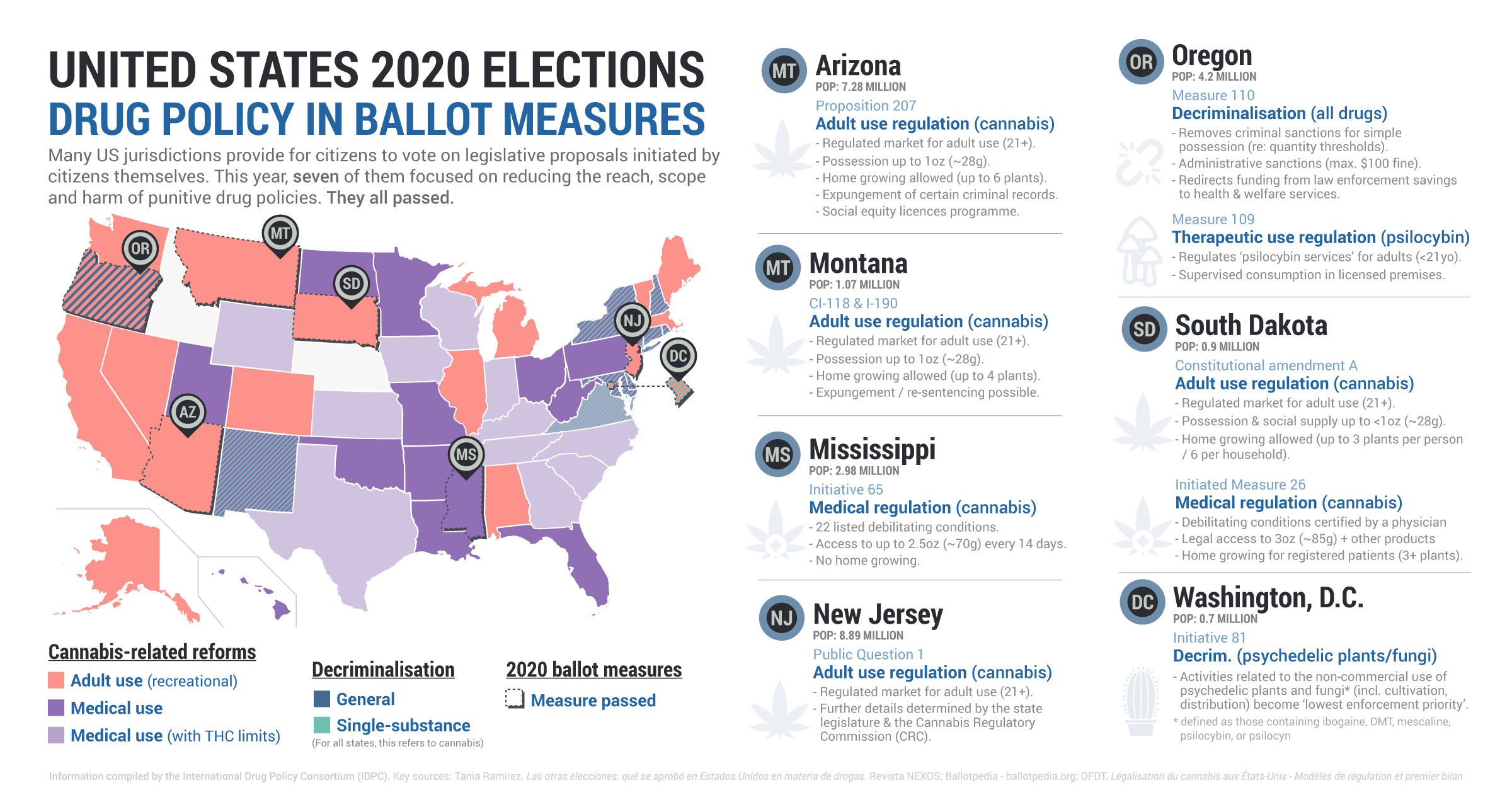

In Arizona, New Jersey, Montana and South Dakota, voters approved the regulated sale of recreational cannabis, continuing a trend that has been going on for several years, bringing the total number of US states allowing recreational cannabis to 15.

The people of Oregon went an important step further and supported a ballot initiative to decriminalise the possession of small quantities for personal use of all currently illegal drugs. This followed in the footsteps of Portugal where decriminalisation in 2001 has led to a dramatic decline in drug-related deaths, as well as infections like HIV and Hepatitis C.

The news from Oregon shows that voters and policy makers are finally waking up to the grim reality of drug policy as usual. After nearly six decades of prohibition and relentless criminalisation of people who use drugs, the failed war on drugs has done absolutely nothing to make a dent in the illegal drug trade. This global business is worth at least 350 billion dollars annually and is entirely controlled by criminal organisations. The drug wars have cost millions of lives and wasted billions in public resources. To make things worse, the arrival of new, more potent drugs like fentanyl have led to new spikes in overdoses and drug-related deaths around the world, showing once more that a hardline stance on drugs that put law enforcement and prosecution over public health isn’t delivering any results.

For the past nine years, I’ve had the privilege of being a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, a high-level group of former leaders in government, civil society and business. My fellow Commissioners and I have long argued that the only solution to stem the tide is to prioritise harm reduction and promote the decriminalisation and, better yet, regulated sale of certain, if not all currently illegal drugs.

Next, week, UN member states will come together in Vienna for an important session of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), the inter-governmental forum where discussions on the direction and content of global drug policy take place. The item on the agenda is a vote on rescheduling cannabis. What sounds like a tedious bureaucratic exercise has enormous significance for correcting a damaging historical error. For decades, without credible scientific basis, cannabis has been scheduled as a substance with negligible medical or therapeutic value that is considered as harmful as heroin or cocaine.

After a long overdue scientific review, the World Health Organisation has recommended limited rescheduling that at least would recognise cannabis’s huge therapeutic potential. A positive vote to remove cannabis from the strictest schedule would signal that the international drug control system, traditionally a driver of repressive drug policies, might be able to reflect with the ever-accelerating reforms happening on the ground. I hope the CND will come down on the right side of science, public health – and history.