Reducing harm with psychedelics

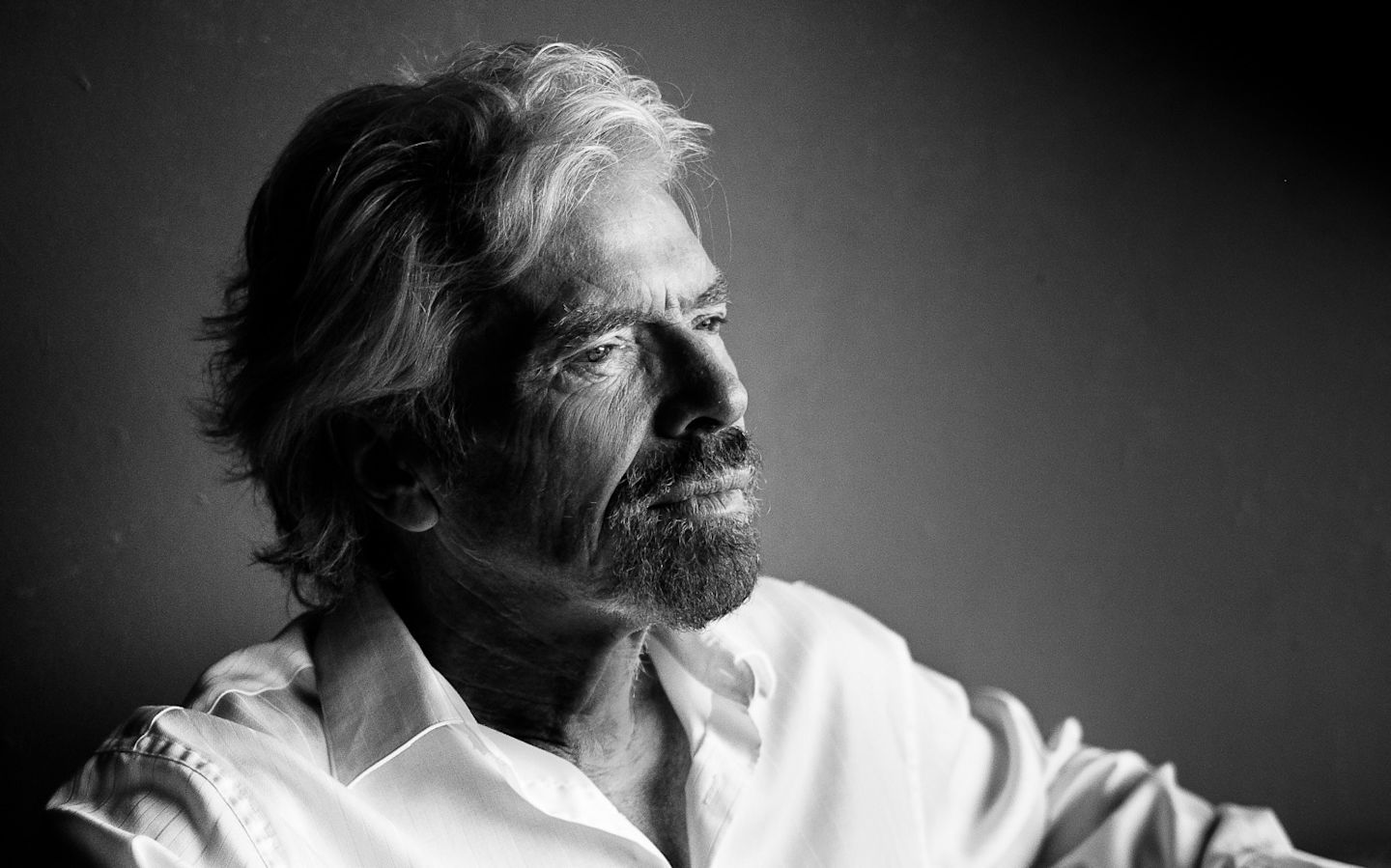

I have for years been a vocal and public critic of the failed war on drugs. As a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, I favour approaches that reduce harm and suffering, end the needless criminalisation of millions, and make communities everywhere safer.

One of the many collateral consequences of drug prohibition is that it has complicated and slowed meaningful research into the potential medical benefits of different, currently illicit drugs – despite rather encouraging signs that psychedelics in particular could represent a quantum leap in the treatment of a range of conditions.

And so I took great interest when I recently joined a group of medical experts, practitioners, users and advocates for an event that discussed the medical and therapeutic uses of psychedelics, from psilocybin to ibogaine or ayahuasca – many of which are plant-based substances with a long tradition of use in indigenous cultures around the world.

While most people associate psychedelic drugs with 1960s and 1970s counterculture, or the pioneering work of Timothy Leary, much has changed since. Of course, the vast majority of psychedelics use is recreational, but I was amazed to hear just how much promise medical researchers and psychotherapists believe psychedelics hold to effectively treat common mental health conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and even drug addictions.

As I learned from experts at the University of California at San Francisco and Johns Hopkins University, ongoing clinical trials involving psychedelics are showing remarkable results, even in people who haven’t responded well to conventional treatment with pharmaceuticals. Regulators are slow to catch up with this “psychedelic renaissance”, as some have called it. And just recently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), declined to approve the use of an MDMA capsule for the treatment of PTSD. But I think as more data becomes available, and as more products are developed, psychedelics-assisted treatment will become commonplace. Perhaps the most touching moment of the event was meeting three US military veterans – Adam Marr, Ryan Roberts, and Tom Satterly – who spoke so movingly of their combat experiences and the psychological trauma that continues to affect them and many thousands of men and women in uniform for years and decades following their service.

The numbers are shocking: at present, at least 22 US veterans are believed to take their own lives every day as a result of the stress and trauma they experienced on the battlefield. The real number may be even higher.

PTSD is widespread among former US troops, as are many other mental health challenges, often in conjunction with substance abuse and homelessness. But once veterans are treated with psychedelics, the results are often remarkable: many report that their previous symptoms weakened or disappeared altogether.

These findings are powerful, and I hope governments will see their value and reduce some of the obstacle and the red tape that prevents this important research from going to true scale.

But it’s important not to lose sight of the bigger picture. Psychedelics may well prove to be an effective new tool in addressing the impacts of trauma on mental health. But it’s the war on drugs itself that is fuelling so much trauma. In addition to finding new ways to treat mental health challenges, we should also aspire to address their underlying drivers. Ending the failed war on drugs is one important step in the right direction.

Interested in learning more about psychedelics? Start your journey at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) or visit Drug Science.